GUERNSEY BREED HISTORY

A product of her island home, which lies in the English Channel off the coast of France, the Guernsey has been developed over two centuries to meet modern dairy requirements. The Guernsey first became popular in English dairies in the late 18th Century. Her renown as an unique producer of rich yellow coloured milk gave her the title "Golden Guernsey". Please read below regarding the origin of the Guernsey cow.

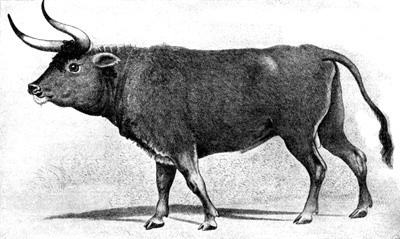

THE GUERNSEY STEER

Earliest known painting in oils of a Guernsey 1841

By permission W Luff

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE GUERNSEY BREED

By W. G. de L. Luff,

Vice-President Royal Guernsey Agricultural & Horticultural Society

Much has been written about the origins of Guernsey Cattle and many claims have been made about the way in which the 'Guernsey Breed' came to be established on a small island in the English Channel. In fact, very little concrete evidence exists about the cattle of Guernsey prior to the nineteenth Century and most theories, such as one that suggests that cattle brought to the island by monks who had been banished from Mont St. Michel in the year 960 A.D. formed the foundation of the present breed cannot be verified and must be regarded as conjecture or pure fantasy.

There may be some truth in the theory that the Isigny cattle of Normandy and the Froment du Léon breed from Brittany were ancestral relatives of the modern Guernsey. Indeed the Jersey, the Guernsey and the Froment du Léon are the only members of the Channel Island sub type of European Blond cattle.

Froment du Léon breed

FROMENT DU LEON CATTLE

The "Froment du Léon" is a high fat producing breed that was common to the district around the town of St. Pol de Leon, in Brittany. It is slender, wheat-coloured, lyre-horned and looks very like the old dun Shetland cows of the early twentieth century. While similar in colour to the Guernsey, it is smaller and of variable conformation. Indeed the Froment du Léon breed society imported semen from Island Guernsey bulls some years ago in an attempt to improve both conformation and milk yield. Breed numbers now indicate that its current status is 'at risk'.

The large Normandy brindle took its name from the rich butter district of Isigny. Isigny cows were heavy producers of a high quality and fine-flavoured milk of a rich primrose colour, while the exterior skin and interior fat carried that yellow pigment so characteristic in the Guernsey breed. The horns curved forward and inward similar to the Guernsey. The breed has been absorbed into the present day Normande.

COTENTINE COW 1862

The main ancestor of the Normande

NORMANDE COW Circa 1900

As far as definitely traceable ancestry is concerned no records exist at all prior to the publication in 1878 of a privately subscribed register of Guernsey Cattle, initiated by the Reverend Joshua Watson of 'La Favorita" and Mr. James James of 'Les Vauxbelets' and based on rules of selection including conformation.

This was followed in 1881 by the publication of the first volume of the 'General Herd Book', which was based upon the principles of American, and English herd books, that is, that entry was allowed to animals that might be 'proved to possess the qualification of purity of race'. Rules for entry must have been rather free as in the preface to the General Herd Book it is stated that 'If pedigrees are short, this arises from the fact that it has not been customary to keep a written record' and 'Stock exhibited at island shows have not been distinguished by names till within the last two years'. The Cattle considered to be of pure race varied in colour including 'white, red and black in any mixture and shade except roan, no instance of which is known to have occurred. Brindle is not uncommon. The nose may be either white or black'.

In 1881 it was decided to publish Volume 1 of the Herd Book of the Royal Guernsey Agricultural and Horticultural Society, the Committee having agreed to take over the work done on the original 1878 and 1879 publications. For 15 years the General Herd Book was published in competition with the R.G.A.&H.S. Herd Book, but the latter increased in general recognition on the island and especially in America.

But what of the history of Guernsey Cattle prior to the nineteenth century? Generally this must have been influenced by two main factors, the natural development of indigenous wild cattle and economic and social pressures on the human community. It is also worthy of note to state here that no 'breeds' of dairy cattle are known to have existed anywhere in the world until the late nineteenth century. Regional differences of "race" in cattle before the eighteenth century were largely the outcome of geographical distance or isolation by natural barriers rather than of deliberate attempts to maintain purity of breed.

Early man discovered how to cultivate wheat and to domesticate wild animals about 10.000 years ago in the Middle East in the Valley of the Tigris and Euphrates and the hills of Turkey. The cattle that were originally domesticated were the large Aurochs which stood up to six feet at the shoulder and were noted for their savage temperament. Cave paintings indicate that the Auroch was variable in colour but generally brown with a darker stripe down the back. It was from these early domestications that Bos Longifrons soon developed and over the next millennia may have come along with human migration from the Middle East probably via North Africa up through Spain and into France. Alternatively a parallel development of the Bos Longifrons type could have occurred from domestication of Western European Cattle. The Guernsey breed is unusual among European breeds in possessing both the bovine haemoglobin B allele and the Beta Casein A2 allele, which are prevalent in African and Asian cattle, indicating that the former theory may be the most accurate. Bones of domestic cattle have been identified in Jersey from approximately 4500 B.C. and there is no reason to doubt that they existed on the other islands at similarly early dates.

The Augsburg aurochs. This painting is a copy of the original that was present at a merchant in Augsburg in the 19th century. The original probably dates from the 16th century. It is not known if the original as well the copy still exist somewhere (Van Vuure, 2003)

In Roman times the introduction of larger Italian Cattle resulted in a cross that had something of the appearance of the Brown Swiss breed, but with a greater variety of colours including mouse and fawn together with black and red. Later on, when the Norse invaders swept along the coasts of Europe and England they brought with them small dun coloured cattle, noted for their rich milk. These when crossed with other races resulted in cattle of broken colour, often yellow and white, and of small size, and these are thought to have populated the coasts of France and the Channel Islands.

Cattle of this type probably existed in the Channel Islands until about the middle of the 18th Century when the importation of Dutch cattle into England started the improvement of the meat producing British cattle. In 1756 Hale published his book 'The Complete Body of Husbandry' in which we find the first description of island cattle. These were 'Very like Dutch Cattle' - the influence of cattle from Holland and Flanders had obviously reached Guernsey as well as England and it is likely that this influence increased the size of cattle in the island.

It appears that during the late 18th Century and up until the end of the Napoleonic Wars, a general degeneration in local cattle occurred due possibly to the uncertainty of the times and the fact that a large number of Guernseymen were then in the employ of the owners of Privateers that sailed out of the Island, or engaged in the trading of wines, spirits and other commodities that could enter the islands from France free of duty and be legally re-exported to England without the imposition of tax.

During this period large numbers of cattle were exported from the Channel Islands to England often under the name of 'Alderneys', local communities being forced to sell in order to obtain grain to feed the population. By this time the cattle had become small again and were not greatly favoured as they did not fatten well, but they could be bought more cheaply than the native English Cattle and together with Normandy cows found a good market in English Dairies. Records show that between 1764 -1775, 6303 cattle were imported into England from the Channel Islands, though many of these are thought to have been French cattle brought to England via the islands in order to avoid customs duty. In fact, the trade with Normandy became so great that it severely affected the trade in island cattle, local farmers being unwilling to sell at the low price of the French cattle, which were, it appears, indistinguishable from island stock.

Alderney breed 1842 [Cow and calf, the property of M. Brehaut of Jersey Colour Plate XIV. David Low. On The Domesticated Animals Of The British Islands Comprehending The Natural And Economical History Of Species And Varieties: The Description Of The Properties Of External Form; And Observations On The Principles And Practice Of Breeding. Pps 767. 1842.]

In 1815, Mr, Thomas Quale in his 'General view of the Agriculture of the Norman Isles' states that up until the time 'No individual has attempted, by the selection of cattle and breeding from them, to attain any particular object'.

About this time, the end of the wars with France and the demise of the 'privateering industry' led Guernseymen to look at new ways of earning a living and in fact many people left the island for new shores, especially America. A good trade had been built up with England and the Guernseyman found that his cattle, now famed for their rich milk were a useful source of income. However, inferior French Cattle were still being imported into the islands and some were exported by unscrupulous farmers as 'pure' Guernseys. Accordingly statutes were enacted in both Jersey (1789) and Guernsey (1819) forbidding the hither-to unrestricted importation of Cattle from France but still allowing free trade in both directions with England.

During the period from 1817, the date of the formation of La Société d'Agriculture (the first Guernsey Agricultural Society), -1877 it is known that cattle of other English breeds were imported into Guernsey. Some were exhibited at the local fatstock shows, two oxen of the Durham Breed being exhibited at the 1862 Fat Cattle Show. The reappearance of black and white as a recognised colour during this period also indicates the possible reintroduction of Dutch type cattle. At the Guernsey Society of Agriculture shows during the year 1820, 31 bulls were seen and only one gained maximum points on the approved scale. It was a Brindle, whose Dam gave the yellowest butter! There was also a black and white bull in the prize list; the judges recommended its use on black and white cows, it 'being of a good breed'. In 1826, 8 animals described as Brindle or black were on show and in 1827 the first prize heifer had a completely white head.

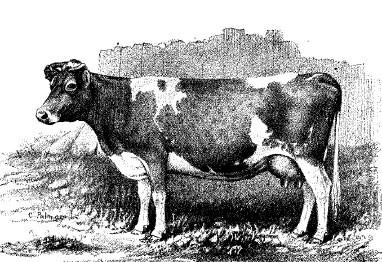

GUERNSEY CATTLE Circa 1850

It was not until 1877 that the door to importation from England began to be closed due mainly to the need to protect the Island from diseases such as Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia and Tuberculosis.

LILLIPUTIAN RGA&HS No 694 - line drawing 1884

The R.G.A.&H.S. finally 'fixed' the colour of purebred Guernseys on February 24th 1883 by adopting an article for the judging scale indicating that this should be 'red or fawn and white' and this has continued to be the accepted colour for the past 120 years. The Golden Guernsey Breed had at last reached an advanced stage of development.

The subsequent history of the breed is well documented in Guernsey and other parts of the world through various Herd Book registers, many of which trace back to the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Prior to this period 'Guernseys' had of course spread far afield but had never been kept 'pure bred' and became mixed with other breeds. It was not until the agricultural improvement societies sought to develop and maintain 'pure' bred Guernseys (cattle that conformed to an accepted general type) firstly on the Island, but very soon afterwards in America and England, that the Guernsey Breed as we know it today was finally established.

MAY ROSE II 3251 P.S.

The cow was then in her prime - a veritable queen and could never be forgotten - Joseph L. Hope in 1891

BILL LUFF

GUERNSEY August 2004

References:

Prentice, E. Parmalee. 1942 American Dairy Cattle. Harper & Brothers

Crump, Felicity. 1955. The Alderney Cow. Where did it come from? What was it like? Where is it now? The Alderney Society, The Museum Alderney C.1.

© This Document is copyright of Bill Luff and the World Guernsey Cattle Federation